Diaz v Karim [2017] EWHC 595 (QB)

The schedule of special damages – never straightforward. The belongings that had to be thrown out, or were taken and not returned. The difficulty in evidencing them, the difficulty in evidencing proof of purchase (who keeps receipts for years? Bank statements or card statements might identify a shop but little more), the perfectly usual absence of a complete and updated, photographically illustrated catalogue of all one’s belongings.

And then, albeit very infrequently, there is the list of special damages that a client hands over that brings on the “we will, of course, argue your case but we need to talk about how this is likely to look to the Judge without any supporting evidence” conversation.

Mr Diaz was not represented in this claim.

The claim was in trespass to goods and to land, arising out of Mr D’s landlord, Mr Karim having changed the locks to Mr D’s rented room in a shared house and having taken his belongings. It should also be noted that there are ongoing possession proceedings against Mr D by Mr K in Lambeth County Court, but that this claim was issued separately in the High Court (QB) as Mr D’s claim form was for a value of £900,000 to £1,000,000.

While Mr K was represented at the trial hearing, he had otherwise been in person throughout. Mr D as Claimant was in person at all times. It is fair to say that this gave rise to certain problems, not least at trial. As HHJ Parkes QC (sitting as a High Court Judge) observes, with the air of weary resignation that suffuses the judgment:

Given the claimant’s evidence about his current attachment to a university department of commercial law, it might have been expected that he would have had some grasp of the practice of English law, or an ability to focus on the pleaded issues. Unfortunately, that proved not to be the case. His trial bundle had not been not agreed with the defendant, despite an order of the court that it should be; it contained a great deal that was of no relevance and omitted some material (for example, the Defence) which was highly relevant; he kept producing undisclosed documents in the course of the trial, and did so without bringing photocopies for the benefit of the court, the defendant’s counsel or the witness to whom he intended to put them; and he told me contentedly on the first day of trial, a Monday, that his witnesses would be coming on the Wednesday. At that stage I had hoped that the trial would have finished within two days, so I urged him to ensure their attendance sooner. In the event I was still waiting for one of his witnesses to turn up at court after 4.30pm on the Wednesday, even after the public entrance to the Royal Courts of Justice had closed. It was clear that the witness would not have arrived until well after 5pm, if at all. I had already allowed the claimant very substantial latitude in the scope and length of his cross-examination, which took many times longer than had been necessary, and I was not prepared to allow the trial to stretch into a fourth day, with all the wasted costs and court time that would have been involved. His lack of grasp of the court process was amply illustrated by his suggestion on more than one occasion that I should simply speak to the witness on his mobile telephone.

There were findings of fact, reached after 3 days of trial. This was after what appear to have been a lot of excursions into various other issues that Mr D had with Mr K (or Mr Rahman, as Mr D insisted upon calling him). For example:

The claimant had a number of fixed beliefs about the defendant, one of which was that an almost identical version of his own copy of the tenancy agreement was a forgery for which the defendant was responsible. Its terms were no different from the version in his own possession, and he does not seem to have asked himself why anyone should take the trouble of forging an agreement in terms identical to those of the supposedly genuine version. It was clear to me from the evidence of Mahfuz Karim, the defendant’s son, who had acted for his father in meeting the claimant on 26 May and handing over the tenancy agreement and house keys, that the version regarded by the claimant as a forgery was simply the version retained by the landlord.

However, it was found that Mr D had a tenancy of a room in the house, as Mr K’s tenant, since 2014. There were allegations about substantial rent arrears from soon after the start of the tenancy, but no specific findings were made on this, leaving that to the possession proceedings, save that even on Mr D’s case, there were arrears.

Mr K claimed to have served a s.21 notice on 30 Sept 2014, giving an expiry date of 30 November. Unfortunately, it would actually have taken effect on 31 December 2014. Even more unfortunately, Mr K did not bring possession proceedings.

On 3 September 2015, it was found, the Defendant had changed the locks and thrown out or taken the Claimant’s belongings. This was supported by a third party witness. Some few belongings were later returned, allegedly damaged. The Claimant apparently slept on the sofa in the living room of the house before forcing entry back into his room on 14 September 2015. The Claimant had called the police on 3 September, and there was a further report to the police of missing belongings on about 14 September 2015.

The question then was the value of the missing belongings and the value of the claim.

The Claimant’s report to the police of 14 September 2014 identified missing items as:

a computer valued at £400, another computer valued at £100, a radio valued at £50, a case valued at £200, a computer valued at £300, photographic equipment valued at £1500, an ANU flag, audio/radio/hi-fi/CD equipment valued at £500, UK and German ID documentation, 3 emerald gemstones valued at £250,000, menswear valued at £1000, and miscellaneous household items such as an iron and a ‘shaving machine’ valued at £200.

As Mr D was in receipt of JSA and had for quite some years survived on payments from students to write their dissertations, JSA and loans from friends and family, the £250,000 of gemstones might raise a question. However, the particulars of claim identified some other items as well, for example 12 CDs of “invaluable academic and political research data/information” valued at nearly £450,000.

For a former academic, historian and bibliophile (reformed) like me, the most startling entries on Mr D’s claimed special damages were:

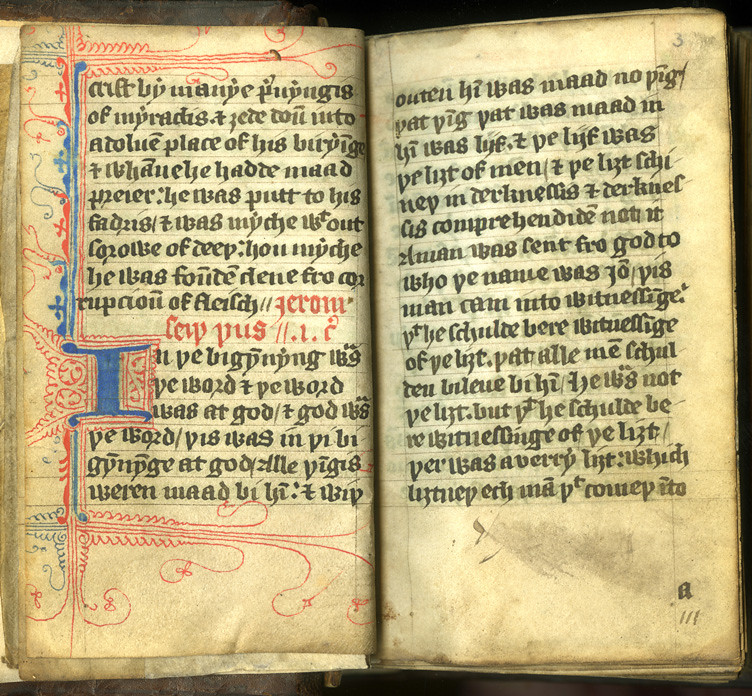

- A 1487 first edition of the Malleus Maleficarum, (one of only four extant copies), bought for 10,000 euros and valued at “between $25,000 and $110,000, depending on its condition.”

- An original 1383 Wycliffe English Bible, bought for between 12-15,000 euros and valued at $1.65 million

The receipts for these were also in the stolen bags of belongings, Mr D asserted. There was also claimed to have been £6,500 in cash hidden in one of the books.

Given the total lack of evidence for these items, the failure to mention them to the police and that Mr D waited some 10 days before breaking back into his room to check on his belongings, HHJ Parkes QC was not impressed:

However, I do not for one moment accept the claimant’s account of what he lost, or of its value. The proposition that I was asked to accept, on the basis of his unsupported and unconvincing evidence, was that as a very impoverished student he had paid a dealer a total of some 25,000 Euros in 2007 or 2008 for two ancient books or manuscripts, Malleus Maleficarum and the Wycliffe Bible; that the books were worth hugely more than he had paid for them, and were in fact, to his knowledge, works of the utmost rarity and value; and that despite his hand to mouth existence and his reliance on state benefits and loans from friends and family, he chose, rather than sell the books or secure them in safety, to keep them, uninsured, in his bags in a Camberwell bedsit. I found that proposition wholly incredible, and I reject it, just as I reject his plainly inflated valuations of his computer equipment, and his claims for the value of the gemstones which he never had professionally valued but claims to have lost. The proposition is all the more incredible when one considers that on his own account it was 11 days before he forced entry to his own room. If he had truly believed that goods of such enormous value had been thrown away by the defendant, he would not have waited one day, let alone eleven, before re-entering his room. I also take into account that the police record of the property which he complained had been taken makes no mention of either Malleus Maleficarum or of the Wycliffe Bible. I cannot accept that he ever owned either book in an ancient or valuable edition, or that he owned valuable emeralds.

Nor do I accept that the claimant lost £6500 in cash. It is difficult to conceive that the claimant, who is a well travelled man and not wholly unworldly, could have thought that the Lauterpacht Centre in Cambridge would have welcomed payment in cash, and I am quite unable to accept his stated reason for keeping such a sum in his bedsit, namely that he did not have time to go to the bank. He was not a man in a high pressure job. On his own evidence he rose in the late morning on 3 September 2015 to go to the IALS library to conduct his research, which (even if he worked late in the evening) does not suggest great pressure of time, and his statements for his account at the Co-operative Bank (up to February 2015) show that he was in the habit of paying cash into his account.

Mr K did enter Mr D’s room and throw out his belongings, including two old “computers, a hard drive, a camera, many academic notes of great personal value to the claimant, political documents relating to his work as cultural co-ordinator of the Azanian National Union, and a number of cultural artefacts, including some coloured gemstones”.

The claim may have been more appropriately pleaded in conversion than in trespass to goods, through there was trespass to land, but nonetheless, the claimant was entitled to damages. There were no submissions from either party on the basis on which damages should be assessed. In the absence of this HHJ Parkes QC decided that

In principle, it seems to me that the measure of damage should be the market value of the goods at the date of conversion or trespass. Given that I reject the claimant’s inflated and exaggerated claim, it is difficult to find a rational basis on which to calculate the market value of that which probably was taken from him, namely two computers, a camera, a Blackberry phone (described in the Claim Form as a Blue Berry), a hard drive, clothes, CDs, three gemstones of uncertain but probably modest value, and a number of modern books. Much though I sympathise with the claimant’s loss of his academic papers, degree certificates, and political and research documents, I do not see how I can put a market value on them. It seems to me that the best I can do is compensate him in very approximate terms for the market value of the lost goods. It would hardly be fair to confine him to the actual market value of (for instance) an elderly computer or a pair of trousers, which would be nominal, and it therefore seems to me that he is entitled to the replacement value of the goods. Doing the best that I can, I assess his loss in the sum of £5000.

Mr D might be awarded part of his costs, but both costs and any set off against the damages award were, it appears likely, transferred to be dealt with in the Lambeth County Court possession proceedings.

Comment

The simple lesson is if you have been either a student or on JSA for many years and have no private means, adding two of the rarest books in the world on to your special damages claim may require a modicum of evidence of actually having possessed the books to obtain an award. This is a lesson of general application.

Also, personal documents are not worth £450,000, or, most likely, anything at all on a specials claim…

I tell ya it’s all gone downhill since the repeal of the Witchcraft Act 1735. Truly the perfidiousness of these judicial witches know no bounds.

Although I do have to question whether the DWP would take issue with the fact that the claimant was living off of (presumably means tested) JSA while having £250,000 of undisclosed precious emeralds in possession. They tend to be a bit strict about capital like that.

Honestly a small part of me kind of wants the claimant’s story to be true just for the sheer oddness of it.

…and then I scrolled up to check the date in case you were in the habit of playing April Fools. But no.

It amazes me, though, that the claimant should be put to strict proof of owning their own run of teh mill belongings in teh event of an unlawful eviction. This ridiculous claim has unfortunately overshadowed what must have been a very difficult set of circumstances when the claimant was evicted.

I wonder why more impatient landlords don’t simply offer to pay tenants off?