Following on from our post on Mohammed v Southwark LBC, here are notes on a further three appeals to the County Court under section 204 Housing Act 1996, all related to decisions on priority need (or lack of it) through vulnerability.

Ward v LB Haringey. County Court at Central London. 22 Feb 2016 (not available elsewhere. We’ve seen the judgment)

This s.204 appeal is particularly interesting for a number of factors. The review was by Minos Perdios – who has been pushing a particular line on the interpretation of vulnerability after Hotak et al – and Haringey’s medical report, such as it was, was by Now Medical, from a Dr James Wilson, a ‘psychiatric advisor’.

Mr W was a single man in his 50s. He had a long history of mental illness. For the last 2 years he had been living with his father, himself in his 80s and with serious health problems, in a 1 bed flat in supported accommodation. Mr Ward slept on the living rom floor. He had applied to Haringey as homeless.

The initial decision was that Mr W was not in priority need. On review, Mr W’s solicitors provided reports from Mr W’s previous psychiatric specialist doctor, his current GP, a psychiatrist and, a bit later, a letter from a CBT psychotherapist from Haringey’s IAPT team, who had assessed Mr W.

All the reports identified a history and ongoing depression and anxiety, currently compounded by his housing situation and by use of public transport and crowds. Mr W had experienced worse episodes in the past, but his condition was deteriorating again. We should also note that the CBT psychotherapist’s letter post-dated the Now Medical report. The recent reports and Mr W’s own statement noted that while he cared for his father when he could, there were also times when his father had to look after him.

The Now Medical report obtained by Perdios for Haringey stated that Mr W’s condition appeared stable with the worst episodes in the past, he was able to care for his father and had ‘well preserved independent living skills. It concluded Mr W “would not meet the threshold for Pereira vulnerability. Indeed I would not make any housing recommendation” and “I don’t think the medical issues would prevent the applicant from fending for himself”. Dr Wilson had not interviewed or met Mr W. (And of course, Now Medical have no place whatsoever to decide whether the vulnerability test has been met or make a housing recommendation. That is for the local authority).

The CBT psychotherapist’s letter stated she was seeing Mr W for recurrent depression and panic disorder, that he could neglect self care, suffered panic attacks on public transport daily.

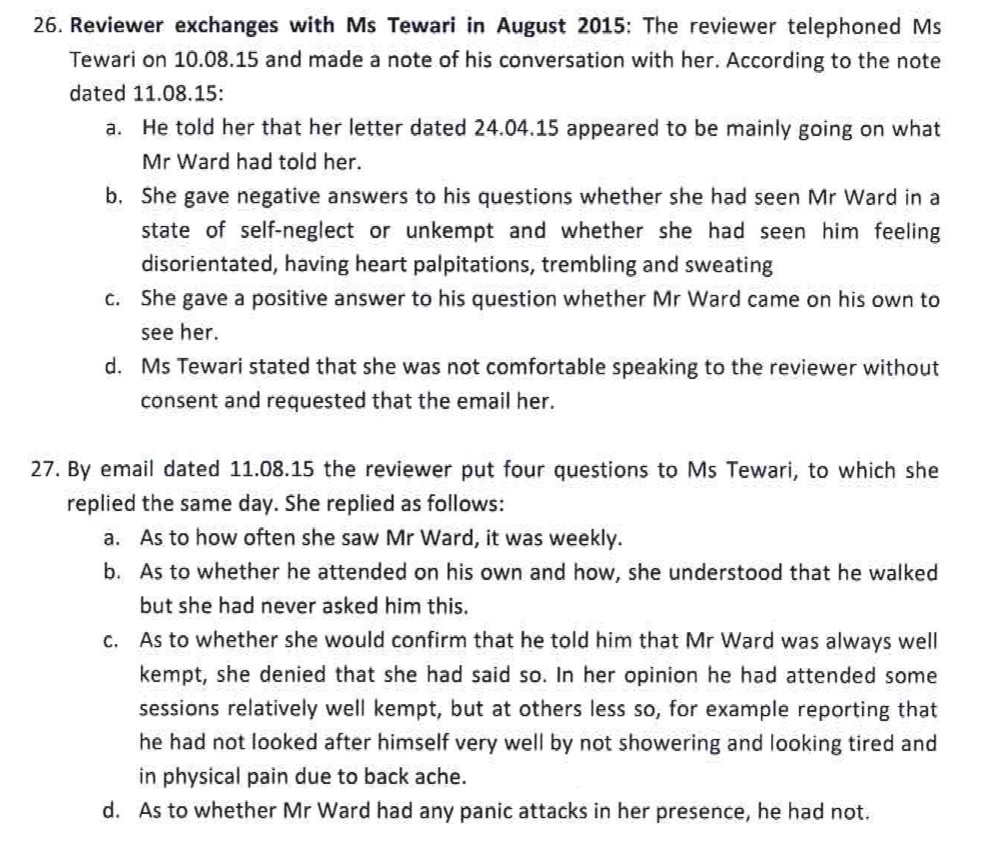

Having received this letter, Mr Perdios called and then emailed the psychotherapist. This needs to be seen in full – the picture is below (or at the top, if you are reading this by email).

Following a ‘minded to’ letter from Mr Perdios, Mr W’s solicitors made further submissions, emphasising that the reviewer had failed to consider the nature of Mr W’s illness in assessing whether he was more vulnerable than ordinarily vulnerable, in particular the nature and extent of his anxiety in social interactions and public spaces. ‘Significantly’ more vulnerable was not only a test of severity but of the nature of the mental illness in the context of homelessness and its cumulative effect. A deterioration of Mr W’s condition when homeless would be significant as it was relative to already clear mental illness, so not merely a generic harm by suffering homelessness.

The review decision upheld ‘not vulnerable’, on the basis that Mr W’s circumstances were “not sufficiently serious for me to conclude you are vulnerable. This is because I am not satisfied that when homeless you are significantly more vulnerable than an ordinarily vulnerable” (sic and see HB v Haringey below). On the mental health issues, it stated ‘the key thing is not actually your diagnosis but how any mental health issues do have impact upon your ability to manage your own affairs and deal with being homeless’. It then mentioned the GP having stated that Mr W did not need overnight care or assistance with daily living. Otherwise, it largely followed the Now Medical report.

On s.204 Appeal, Mr W argued that:

i) the reviewer misapplied the test for vulnerability as per Hotak

ii) the reviewer failed to take proper or lawful account of the evidence

iii ) the decision was irrational, disproportionate and frustrated the policy of the legislation

iv) the reviewer failed to provide adequate reasons as to what is ‘significantly more vulnerable’ in determining that Mr W was not vulnerable

Held.

On any fair and reasonable reading of the medical and other information obtained by the reviewer, in particular information relating to Mr W’s history of mental illness, by reference to the comparator of “the ordinary person if made homeless” Mr W is “significantly more vulnerable than ordinarily vulnerable” if rendered homeless.

On the facts of this case, the reviewer’s contrary conclusion is not consistent with the application of those Hotak criteria, is not reasonably tenable on the facts and is irrational.

Further, the review did not take proper account of the evidence. It was overly weighted by the Now Medical report, which was itself based on the medical information provided some months previously. Dr Wilson’s report could not be taken as expert evidence as to Mr W’s condition as he had not examined Mr W. The report predated Hotak and was predicated on the wrong comparator. It further reached conclusions that simply ignored Mr W’s own statement and medical history in respect of ‘independent living skills’ and ‘coping skills’, mis-stating his reasons for returning to London and that Mr W also relied on his father’s care. These failings should have been apparent to the reviewer.

Despite Hotak supervening, Now Medical were not asked by the reviewer to reconsider in view of the Pereira threshold no longer applying, nor was an update asked for in view of the CBT psychotherapist’s letter.

The review did not address the GP’s report properly – it had addressed ‘coping’ solely in the context of Mr W being in his father’s flat, not homeless.

Grounds 1, 2 and 3 of the appeal made out.

The Judge was not prepared to reach a further definition of ‘significant’, save that on any interpretation, Mr W’s vulnerability was with the meaning.

Appeal allowed, review decision quashed.

HB v LB Haringey. Mayors & City of London Court, 17 September 2015 (Housing:recent developments. Legal Action December 2015)

HB was a single 45 year old. He was from Algeria where he had suffered torture. He continued to suffer from chronic PTSD and recurrent depressive disorder. A consultant described him as chronically disabled by reason of his physical and mental disorders.

He applied to Haringey as homeless, prior to the handing down of Hotak/Johnson/Kanu by the Supreme Court and was found not in priority need. On review, Haringey indicated it was minded to find him not vulnerable on the Pereira test. In the meantime, Hotak had been handed down and further submissions were made on the effect of that judgment and Mr HB’s conditions.

Haringey’s review decision stated that Mr HB’s “circumstances are not sufficiently serious for me to conclude that you are vulnerable. This is because I am not satisfied that when homeless you are significantly more vulnerable than an ordinarily vulnerable’. (sic).

On s.204 Appeal, HHJ Lamb QC held:

It was impossible to discern from the reviewing officer’s decision:

- How he defined vulnerability

- What, if any attributes of vulnerability he had ascribed to the ordinary person comparator.

- How he defined the word ‘significantly’ – where on a spectrum of meaning between ‘noticeable’ and ‘substantial’ he had placed ‘significantly’.

- Whether he considered HB to be more or les vulnerable than the ordinary comparator.

- Whether he considered HB to be invulnerable or without vulnerability, and

- If he considered HB to be more vulnerable than the ordinary comparator, whether and to what extent and why the difference was insignificant.

Review decision quashed and appeal allowed.

SS v London Borough of Waltham Forest County Court at Central London. 5 September 2016 (Thanks to Garden Court and Tim Baldwin for the note)

SS had left her home due to severe domestic violence which had left her with chronic mental and physical health problems. She had been provided with supported accommodation in a specialist refuge. This was coming to an end and she applied to Waltham Forest as homeless.

Waltham Forest decided SS was not in priority need as compared to the ordinary homeless person, as per Hotak. Waltham did however agree that the appellant was disabled within the meaning of the Equality Act 2010 where the disabilities arise out of domestic violence and so the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) was engaged. The not vulnerable decision was upheld on review.

On s.204 appeal, the Judge allowed the appeal.

The Local Authority had not lawfully applied the test of vulnerability from Hotak and had not completed a composite assessment, as it had not taken into account the risks of harm presented to the appellant arising out of the risk of loss of specialist support and accommodation, which rendered the appellant significantly more vulnerable than an ordinary homeless person of robust health.

Further, while Waltham Forest had accepted the appellant’s disabilities had arisen out of domestic violence but had only considered the protected characteristic of disability in their PSED assessment. The assessment had failed to address the protected characteristic of sex which was directly linked to domestic violence, given the judgment of Lady Hale and Lord Neuberger in Hotak, such that it could not be said the PSED had been lawfully discharged.

Decision quashed.

0 Comments